Preparing a Thesis for the Ages - A Checklist

Many graduate students these days do not put much effort into the preparation of their final thesis. At the University of Alberta’s ECE Department we have an internal exam consisting of the student’s supervisor and committee, who decide if a thesis is good enough for a full defense with a chair and external examiner. During my internal exam, one of my committee members commented how many students take a “stack of papers” approach to their thesis wherin their thesis is just their published papers with minimal formatting or effort taken, as I had put extensive effort into my thesis leading up to the exam.

Granted, there is a good reason for this: Conservation of energy. These days its unlikely (at least in CS and ECE) for very many people who are not examiners to view a PhD student’s thesis in much depth so it may not be worth the effort to make it look nice, especially if you’re in the middle of a job hunt. However, it is nevertheless a worthwhile endevour as your thesis will not only outlive you, but help to define you as an academic.

So, what did I do? Two things: I made my PhD a ‘living document’ and followed a checklist.

Disclaimer: I’m not saying this checklist got me the department-level award for best thesis. I got that award because my thesis contained 6 papers that had already been accepted to some conference - usually an A* one at that.

First, at the start of my PhD program I made an overleaf copy of my MSc thesis, gutted the contents, and changed MSc -> PhD where applicable. Every time one of my papers got published, I added its LaTeX contents to my PhD thesis overleaf after acceptance of the camera-ready manuscript to avoid insanity. I also made sure all the floats/figures semi-worked, e.g., each paper was its own chapter, got its own folder in overleaf, so I had to adjust the paths in ‘\includegraphics’ commands. This meant my thesis content gradually grew over my program, rather than needing to all be cobbled together at the last minute.

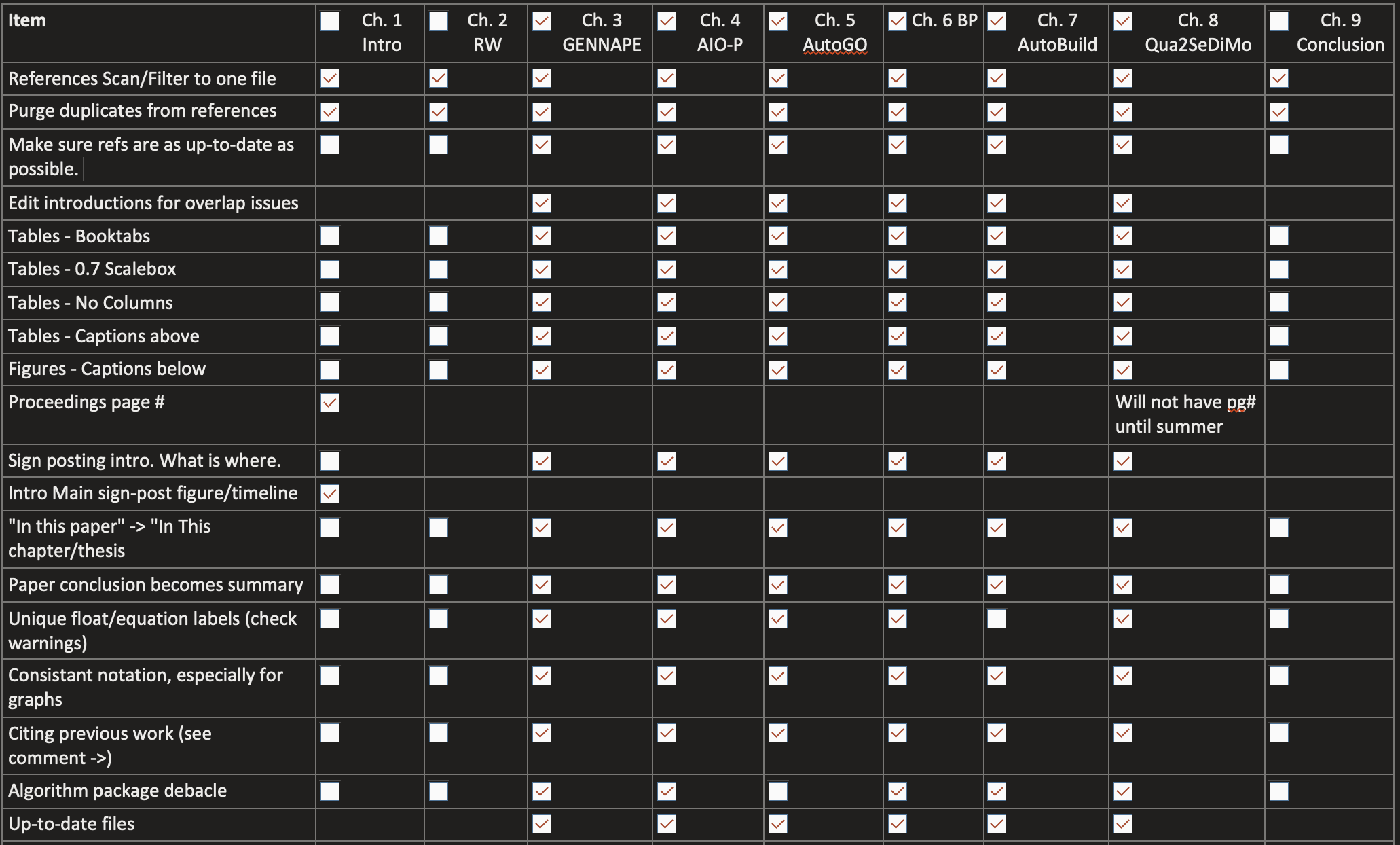

Second, I put together a checklist of things to do, either across the entire thesis or to each manuscript as it was translated from standalone paper to thesis chapter. After I defended my thesis in Edmonton, Alberta and before I moved to Baton Rouge, Louisiana, I made a note to pass this list onto my future students. Originally, this was just a simple OneNote table:

During my final defense, I got a few positive comments about my efforts. However, that table was designed for my eyes - I know what every element means, and why it is necessary but you may not. So, rather than just providing it, I’m sharing my guidelines as an online resource here, starting with five broad points:

1) First, treat your thesis as the story it is. Unlike your individual papers which are stand-alone when submitted by themselves, they don’t have to be stand-alone as part of your thesis. If, for instance, one of your early contributions has a limitiations section enumerating your future work, and a later chapter tackles that issue, make mention of it in the earlier chapter: ‘…this is definitely a promising direction for future work, which we handle in Chapter X.’ Likewise, if one contibution builds off prior work directly, don’t be afraid to reference it, because it helps strengthen the case that your work is in a coherent direction.

2) Consolidate and update your references. Very likely different papers you’ve written cite the same works of others, e.g., NAS survey. It is best to consolidate all of your references into one ‘.bib’ file and remove duplicates. Further, make sure you’ve got the updated version of each reference - we live in an era of ArXiv. When you publish your paper you might cite some arxiv preprints but by defense day those manuscripts may have found a home in a conference and given a fancier bibtex, so updating them will help your thesis stand the test of time.

3) One reason where students get stuck is that taking the time to form a coherent overall thesis introduction can be daunting, because its not just talking about one single paper, its telling and selling the story of many papers. Honestly, here’s my advice to make this a cinch: Usually, there are two halves of a scientific paper’s introduction. The first half establishes the problem and gives reason why the reviewer should care about it. The second half talks about what you did by detailed contributions. Those first paragraphs of each introduction should be blended together to find the initial basis of your overall thesis intro, and then once you have a coherent story idea that ties all your work together, go from there. However, also be sure to edit the introduction section to each chapter (paper) so there is not too much repetition.

4) Tables and Figures. This is an area where a little bit of work can make things look so much nicer. The key is to just be consistent (and use the booktabs package). If your thesis consists of two conference papers which have different rules on tables (e.g., captions above or below the float), then just pick one and make it consistent throughout the entire document. You would usually strive to have consistent float formatting for a paper submission, so do so here too. Same with the scalebox parameter, make it consistent (I used 0.7) and don’t be afraid to use the ‘landscape’ environment in LaTeX for handling large tables.

5) Notation consistency and labels. What this means is to, if possible, go through the methodology sections of your papers as they are in your thesis and make the proper adjustments so that they have consistent notation. As you would expect, this can be a pain and also time-consuming. My PhD thesis involved a lot of graph and GNN equations, so one thing I did to alleviate this was to write a common background subsection in the related work, making minor mention to where some equations would be used later in the thesis. Likewise, I also edited those future chapters to reference the related work, or even chapters of previous papers, e.g., in Chapters 7 and 8.

Additionally, here are some more minor points or details to take into consideration:

1) Early on, find an existing LaTeX template for your given university. Each university will have slight different specifications - formatting, spacing, AIGC policy, etc. See if your university provides an up-to-date version of their specifications as a LaTeX template or if a third party has done so. Special thanks to Daniel Aldric for providing this in the case of UAlberta. Here are some links for my LSU students.

2) These days we cannot do much ‘sign-posting’ in papers, e.g., ‘The rest of this paper is organized as follows…’ due to page constraints for conferences. For your thesis though, you can, and it helps clarity. So do this in the introduction to the dissertation as well as each chapter. For the thesis introduction, remember how we talked about how each paper’s introduction is split into two parts, the second of which is your contibutions? Use the second half as part of your sign-posting: ‘Chapter X introduces method Y, which has contributions A, B, C…’. Further, it helps to create a roadmap figure which tells a viewer what each chapter will contain as well as potentially their ordering. Credit to Puyuan Liu’s MSc thesis for this idea.

3) ‘In this paper…’ becomes ‘In this chapter…’ while paper conclusions become chapter summaries.

4) If you papers use conflicting LaTeX algorithms packages, that is a beast you should slay at the earliest possible opportunity.

5) LaTeX > Word. There is no discussion on this matter, it is just a simple fact.

Finally, if anyone else has anything to add to this list, feel free to give me a shout! Its by all means not definitive and I’m definitely open to adding to it!